Error Feedback — The Third Pillar Of Learning

Making mistakes is the most natural way to learn. The two terms are virtually synonymous because every error offers an opportunity to learn.

The only man who never makes a mistake is the man who never does anything.

- Theodore Roosevelt (1900)

It would be practically impossible to progress if we did not start off by failing. Errors always recede as long as we receive feedback that tells us how to improve. This is why error feedback is the third pillar of learning, and one of the most influential educational parameters: the quality and accuracy of the feedback we receive determine how quickly we learn.

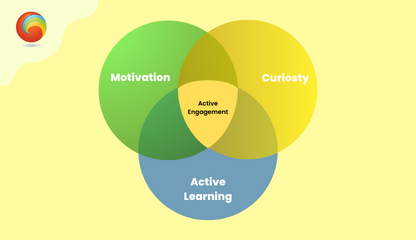

SURPRISE: LEARNING'S DRIVING FORCE

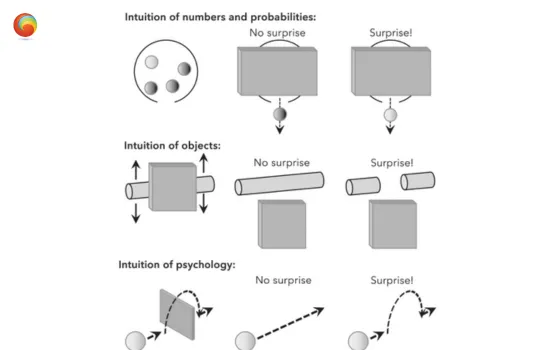

No learning is possible without an error signal: “Organisms only learn when events violate their expectations.” In other words, surprise is one of the fundamental drivers of learning.

No surprise, no learning: this basic rule now seems to have been validated in all kinds of organisms, including young children. Remember that surprise is one of the basic indicators of babies’ early skills: they stare longer at any display that magically presents them with surprising events that violate the laws of physics, arithmetic, probability, or psychology (see figure below). But children do not just stare every time they are surprised; they demonstrably learn. Learning is active and depends on the degree of surprise linked to the violation of our expectations.

Learning by error feedback is universally widespread in the animal world, and there is every reason to believe that error signals govern learning from the very beginning of life.

GRADES: A POOR REPLACEMENT FOR ERROR FEEDBACK

According to learning theory, a grade is just a reward (or punishment!) signal. The grade of an exam is usually just a simple sum, and as such, it summarizes different sources of errors without distinguishing them. It is therefore insufficiently informative; by itself, it says nothing about the reason why we made a mistake or how to correct ourselves. In the most extreme case, a grade F that stays an F provides zero information, only the clear social stigma of incompetence.

These students are not necessarily less intelligent than others, but the emotional tsunami that they experience destroys their abilities for calculation, short-term memory, and especially learning.

Implementing a growth mindset does not mean telling every child that he or she is the best under the simple pretext of nurturing their self-esteem. It means drawing attention to their day-to-day progress, encouraging their participation, rewarding their efforts, and explaining to them the very foundations of learning. That all children have to make efforts, that they must always try out a response, and that erring (and correcting their errors) is the only way to learn.

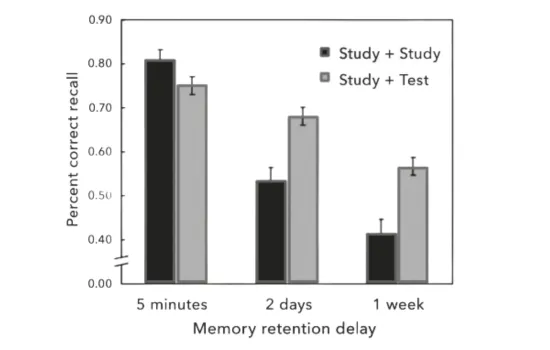

If grades are hardly effective, then what is the best way to incorporate our scientific knowledge of error processing into our classrooms? Testing. Regularly testing students’ knowledge, a method referred to as “retrieval practice,” is one of the most effective educational strategies. Regular testing maximizes long-term learning. It is a direct reflection of the principles of active engagement and error feedback.

Let’s leave the last word to Daniel Pennac:

TEST THYSELF

Here is an example: Imagine that you have to learn some words in a foreign language, such as qamutiik, the Inuit word for “sled.” One possibility is to write the two words side by side on a card in order to mentally associate them. Alternatively, you could read the Inuit word first and then, after five seconds, the translation.

Note that the second condition reduces the amount of information available: during the first five seconds, you see only the word qamutiik, without being reminded what it means. However, it is this strategy that works best.

Why? Because it forces you to think first and try to remember the meaning of the word before you receive feedback. Once again, active engagement followed by error feedback maximizes learning.

Self-testing is one of the best learning strategies because it forces us to become aware of our mistakes. When learning foreign words, it is better to start off by trying to remember the word before receiving error feedback than to merely study each pair (top). Experiments also show that it is better to alternate periods of studying and testing than to spend all of one’s time studying (middle). In the long run, memory is much better when rehearsal periods are spaced out, especially if the time intervals are gradually increased (bottom).

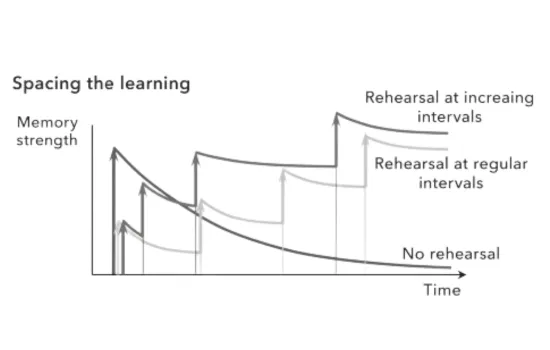

THE GOLDEN RULE: SPACING OUT THE LEARNING

The best way to ensure retention in the long term is with a series of study periods interspersed with tests and spaced at increasingly large intervals. The rule is simple, and all musicians know it: fifteen minutes of work every day of the week is better than two hours on a single day per week.

The rule of thumb is to review the information at intervals of approximately 20 percent of the desired memory duration — for instance, rehearse after two months if you want a memory to last about ten months. The effect is substantial: a single repetition of a lesson at a delay of a few weeks triples the number of items that can be recalled a few months later! To keep the information in memory as long as possible, it is best to gradually increase the time intervals themselves.

Each review reinforces learning. It refreshes the strength of mental representations and helps fight the exponential forgetfulness that characterizes our memory.

Above all, the spacing out of learning sessions seems to select, out of all the available memory circuits in our brain, the one with the slowest forgetting curve, that is, the one that projects the information farthest into the future. Repetition has other benefits for our brain: it automates our mental operations until they become unconscious.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

What are the 4 pillars of training?

- Knowledge: Acquiring the necessary information and understanding of the subject matter.

- Skills: Developing practical abilities and expertise through practice and hands-on experience.

- Attitude: Cultivating a positive mindset, motivation, and a willingness to learn and improve.

- Behavior: Incorporating learned knowledge and skills into one’s actions and daily practices.

-

What are the 4 pillars of education in India?

-

The four pillars of education in India are:

- Learning to know: Acquiring knowledge, critical thinking skills, and a broad understanding of various subjects.

- Learning to do: Developing practical skills, vocational training, and the ability to apply knowledge in real-life situations.

- Learning to be: Fostering holistic development, personal growth, and nurturing values, ethics, and character.

- Learning to live together: Promoting social awareness, empathy, inclusivity, and the ability to interact harmoniously in a diverse society.

-

Who gave the four pillars of learning?

- The four pillars of learning were proposed by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in the Delors Report titled “Learning: The Treasure Within” in 1996.

-

What are the 4 pillars of cognition?

- There is no widely recognized or established framework that specifically identifies the “four pillars of cognition.” Different models and theories may propose different components or pillars within the field of cognition, but there is no universally agreed-upon set of pillars.